Welcome to Madam Ambition, tell us about yourself?

I’ll briefly start with the origins of my parents. My parents are originally Iranian and Baha’i. Because of the persecution, they had to leave Iran in the 70s. My mom grew up in Spain, my dad grew up in the Philippines and they randomly met in Nigeria, got married in Equatorial Guinea and had me in Canada. When I was about six years old, I moved to a place called Umtata, a province in South Africa. I spent most of my childhood in South Africa, but every year for about six months I would go to Canada. My parents moved to South Africa for a couple of reasons. One was for service but also because my mom is a doctor and she really wanted to help in the public hospitals during that time because in the early 90s, there was still quite a lot of instability.

What forces influenced you the most?

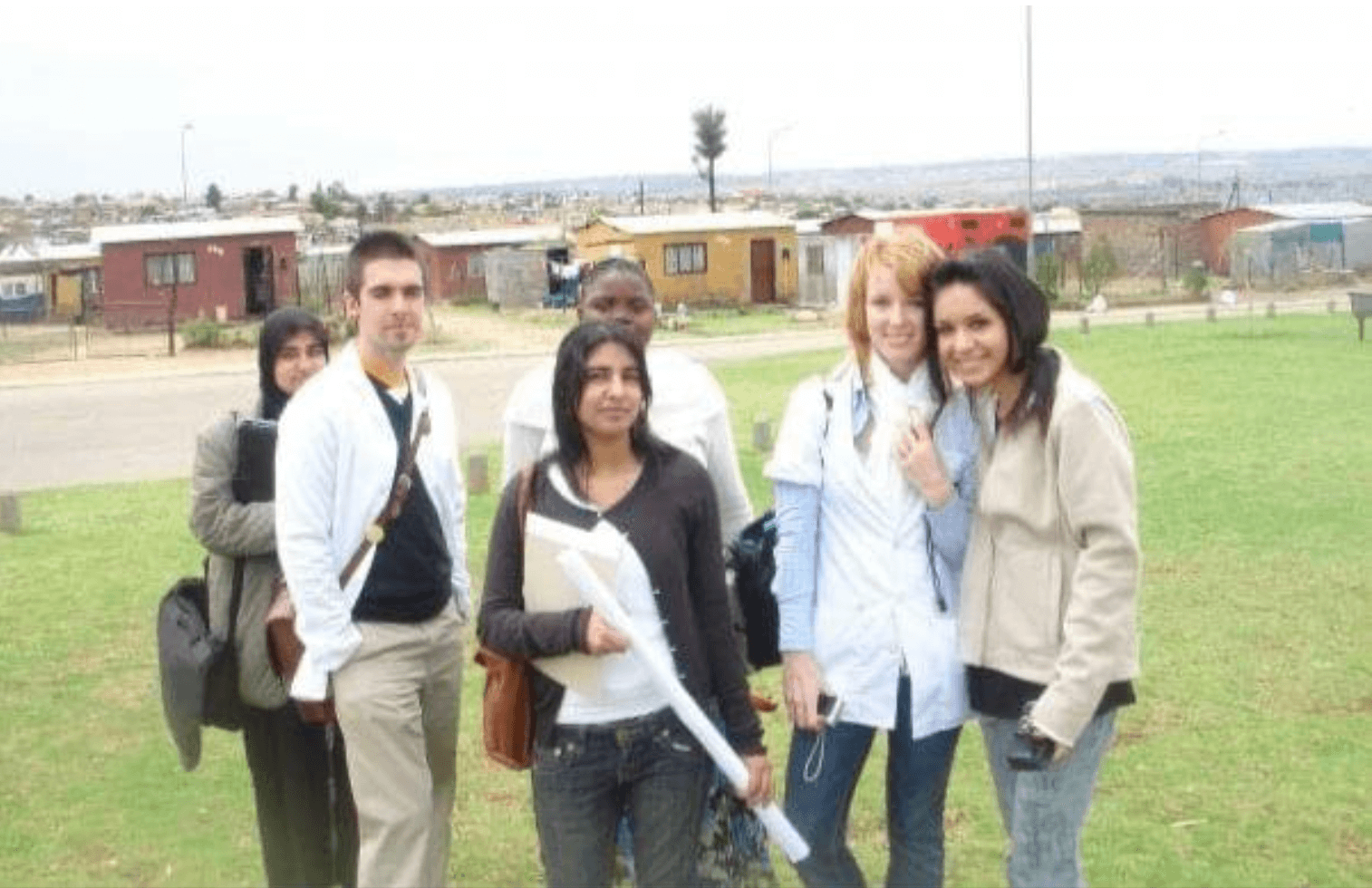

I was really influenced by watching my mom with how passionate she was about medicine. When I got a little bit older, I was really lucky to be able to travel with her throughout South Africa to support a variety of health campaigns. She was really passionate about HIV/AIDS work and so she would get into the car with one of her nurse Baha’i friends and they would literally travel throughout South Africa and participate in conferences to talk about HIV/AIDS in the local townships and villages. I was really lucky I was able to come with her. I really remember how passionate she was about this and that kind of stuck with me –– the passion that she had for medicine. I thought I could do that too one day. So Umtata, we moved to Botswana to a little city called Gaborone and we lived there for probably about six years, and I went to high school there.

Did you like school? Did you already have a knack for Sciences at this point?

Yes, I did. I gravitated towards the sciences in high school and I really tried to pick the right subjects so that I could study medicine at the university upon graduating. When I got accepted into university I studied in South Africa at the University of Pretoria and I finished my medical degree there.

Wait, within college, you finished your medical degree? How does the system work in South Africa?

Yep, so you apply for university based on your grade 12 results and then if you have done well and they accept you, you go straight into medicine so there’s no like undergrad or anything that you need to do before you get into medical school. I think in the States, you have to do some sort of degree before but in South Africa, you can go straight in. So in the first year, you do basic math, basic biology, chemistry, physics. In the second year, you do things like anatomy, a bit of pharmacology, and a little bit of microbiology. In the third year through the sixth year, you attend blocks. So there’s a cardiology block, a pulmonology block, a neurology block, a pediatrics block, a surgery block, etc. Afterward, you start rotating in the hospitals and you spend half your days in lectures and the other half in the hospital doing rotations and practicing basic skills. So I did that and then when I was in my final year of medicine I got married.

So you got married? How did you meet your husband?

In the university, we had a Baha’i society and I was pretty active in it while I was there. Ariel is Baha’i. He came up to Joburg when I was probably in my second last year of medical school to visit a friend of his and then we connected because of the Baha’i community and how small it is.

So what did you do after school?

So after medical school, you have to serve the government for three mandatory years. That was the year that I had to choose where I was going to do my internship for the next two years and then do a community service year.

Do you have to apply to work at certain places or were your internships preset?

No, you’ve got to apply and it’s really, really difficult to get a post because of corruption. A doctor can finish medical school, and then they could have no job for up to six months, even though the country is in such dire need of doctors. The government says they don’t have money to pay doctors or that there are no posts available. It’s not even like the private communities. It’s the rural villages where they really need doctors and there’s apparently no funds to pay them.

When I started specializing in family medicine a couple of years ago I was told that they couldn’t pay me for the first year, because they didn’t have money. I ended up dropping out of that system and I worked in the private sector instead which is quite sad, because in South Africa, the healthcare system is divided up into the public and private sectors. The public sector is where there’s a huge need, accounting for probably 90% of the population. 10% of the population seeks private medical care. But it’s difficult to find a job in the public sector because you’re paid by the government. I had to leave the public system to work in the private system because there was just no money in the public system “apparently.”

Where did you end up getting your internship?

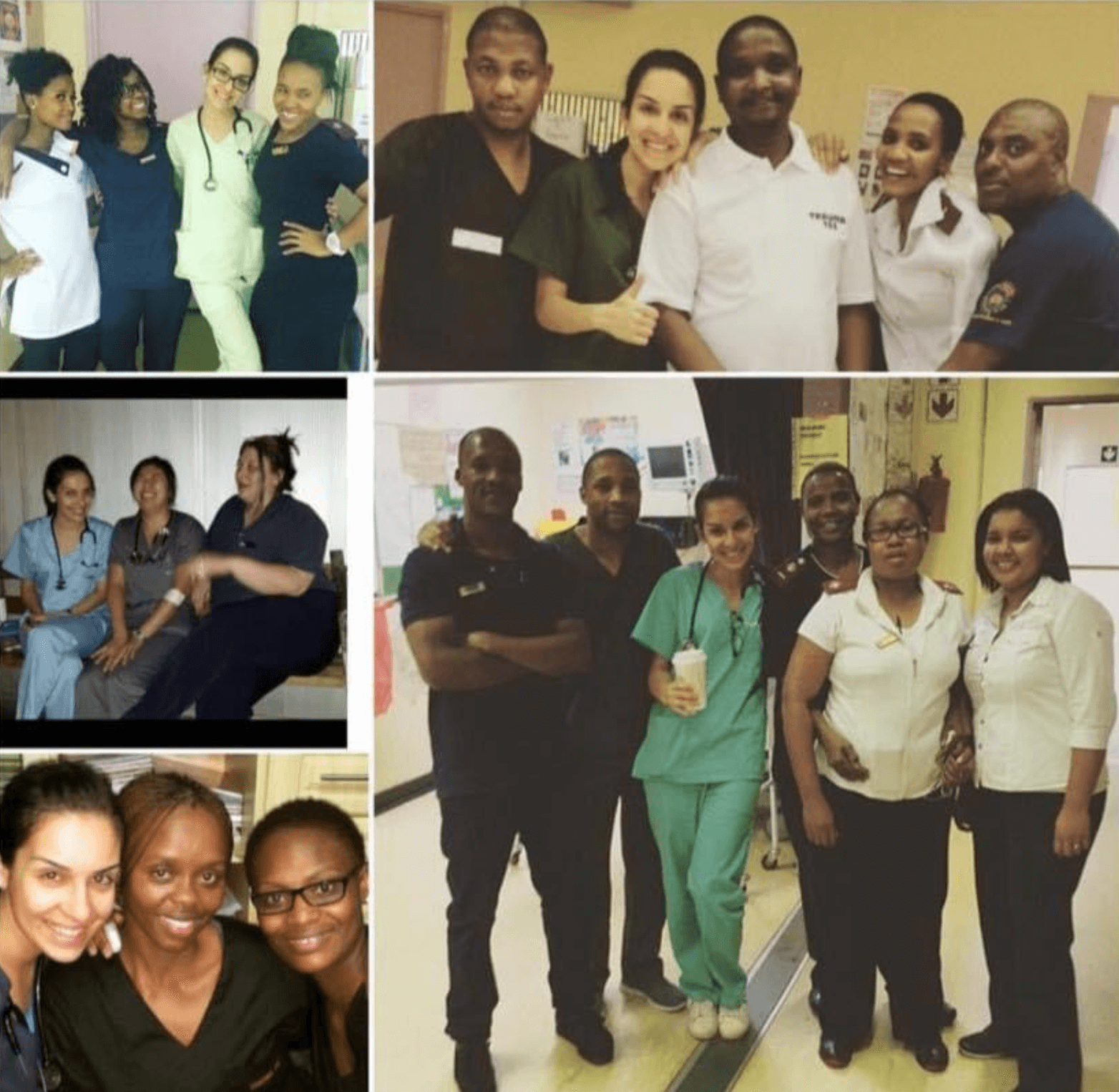

For my internship, I worked in a public hospital in Johannesburg called Charlotte McVicker academic hospital. I worked in trauma hospitals where you see victims of gunshot violence and stab wounds and things like that. They have dedicated trauma hospitals and it’s crazy working there. Like, you know, this whole load shedding thing, when the electricity was off? So it would go off in the hospitals you’d be literally using your flashlight to put in intercostal drains to save lives.

You didn’t have generators?

No, isn’t that crazy? For patients that were on ventilators, you’d have to disconnect the ventilator and manually ventilate them with your hand and a bag-mask until the electricity came back on.

What happens when this happens?

It’s all hands on deck. The nurses, the doctors, and medical students will help. When load-shedding happens the ambulances need to be diverted. They don’t bring patients in because we don’t have electricity but then what they do is they wait outside the hospitals because there’s nowhere else for them to take patients. Eventually, we’d have to bring the patients in because they’re dying outside and need to come in. It’s crazy. I worked in a place called Hillbrow. I don’t know if you’ve heard of Hillbrow but it’s probably the most dangerous workplace in the world. There’s the most violence in the world, trauma-related, gunshots, stab wounds, you know, things like that. So I worked in that area for two years and that’s where I did my internship.

How was that like, was that emotionally draining for you? Did you want to do want to pursue it?

It was really, really, really, really difficult to say the least because you’re totally understaffed. There are so many patients and not enough beds. It looks like a warzone honestly. There are patients on the floor. There are patients everywhere and it’s hectic. You’re so tired and overworked and lots of accidents happen. You get blood on your face, needlestick injuries, and things like that and then you’ve got to go on post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV and stuff like that. It’s really hectic working in the public hospitals, but especially in trauma here.

Do they have a high turnover of staff?

No, there are very dedicated people that trudge through year after year, but when you’re an intern you stay in one department for only six months.

So you did that for six months and then you wanted to move on?

Yeah. I moved on to medical emergencies for six months, so that’s different, that’s more hypertensive emergencies, your diabetic emergencies, strokes and things like that. Trauma was just so hectic. It was nice and I enjoyed the adrenaline of it all but I wanted a change because it gets quite busy.

And so after you finished your community service year, what did you want to do?

After community service, you can really do anything you want, you can apply for the public sector and hope that you get a post. You can also move on to the private sector. But I was tired so I decided that I was just going to take a break for a year. I wanted to travel. So Ariel and I both quit our jobs and then we ended up traveling the world for a year. We went to California for three months then we went to Southeast Asia for six months and ventured to Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand, Laos. We mostly did Southeast Asia and then Canada and the US.

Was this like a chance to just enjoy yourself or was there some sort of mission behind it?

We never really left with the intention of living elsewhere. After three years of working for the government where you have calls and mandatory hours and things like that I just wanted a chance to breathe.

So you came back to South Africa. Did you already have a job lined up?

When we were towards the end of our trip that year, I started interviewing for emergency medicine again. I would sit in at Bosch at like 2 AM in the morning and take interviews in South Africa. I wanted to come back to the emergency department in the trauma units again so I came back and started working back in the public hospitals in South Africa.

How long did you do that for?

So I did it in 2017-2018, but then I decided that maybe family medicine might be a bit easier because you can choose your own hours. I wanted to be able to balance family life with work life so I moved to the private sector at that point to do something a little more chilled. I wanted to start having a family and because I knew it would be so hectic being pregnant and working in the emergency department I didn’t want to go on that route.

How did you get into a different area of medicine?

My mom owns a practice in Johannesburg. I reached out to her and asked if I could do a couple of hours at her office and she said “yes, please” so I ended up working for her.

And you only wanted to do a couple of hours or full time?

Initially, I did work full time for her but then I felt pregnant. So, I went on maternity leave for like, a couple of months. When I came back I just wanted to work like two days a week and just for half days because I wanted to be with my kid. I’ve pretty much done that for the last three years as I’ve only worked two days of the week and half days. I guess that’s the nice thing about having studied medicine is that it gives you that flexibility and so I can kind of just work anywhere right now when I want to and be with the kids when I want to. I’m pretty much more momming than I am doctoring at the moment.

When COVID came to South Africa, how did that impact your work life?

It became really busy. My mom had COVID twice and so did my sister, she’s also a physician.

And what do you want to do next?

Being a doctor gives me a lot of flexibility. I would ideally like to stay at home with my kids a little bit longer. My youngest is seven months old now and my oldest is going to be three next week. When they go to school, I’d like to work a little bit more or I’ll start studying because I do want to write my Canadian exams too.